In the 73rd precinct in Brownsville, reporting a crime goes like this: you step through a brick entryway into a cramped, dimly-lit room and you wait there, staring at a wall.

A set of double doors and a window break up the metal barrier, but red-lettered signs remind you that you aren’t allowed to go through. On the other side of the plexiglass, police dash around the station’s spacious interior. They pay little mind to the lobby, where the four plastic seats are often taken, leaving everyone else to stand on the stained linoleum.

An officer comes to help, eventually. He opens the door halfway to ask people what they need, one by one. But therein lies another problem: the tiny, triangular waiting room has no privacy. So, everyone can hear every fearful crack in an old man’s voice as he tells how he’s lost $2,700 to an online scam. And they can see every tear on a woman’s face when she rushes into the precinct after learning that her child is in trouble.

In a neighborhood where violent crime ranks third-highest in Brooklyn, and where public trust in police is down from last year, according to NYPD data, both citizens and police complain that the 73rd precinct’s design isn’t doing them any favors. For Brownsville residents like Digna Layne, who felt so demoralized by her experience filing an incident report that she joined the precinct community council to fix the issue, the situation demands change.

That’s why Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams and City Council Member Alicka Ampry-Samuel are funneling a joint $1.25 million into renovating the 73rd and three other Central Brooklyn precincts, they announced at a press conference with Mayor Bill de Blasio in August. Between now and 2020, the city will redesign the public entryways of the 71st, 73rd, 75th and 77th precincts. Depending on budget priorities, they may also add community meeting rooms to one or more of the precincts, dedicating a space for residents to obtain resources and congregate safely, Ampry-Samuel said.

Inspector Rafael Mascol, commanding officer of the 73rd precinct, hopes the redesign will make it easier for community and police to bond. “My desire is that when people come here, they say, ‘Wow, this is the friendliest precinct in the entire city,’” he said.

Others are skeptical. “That’s beautiful that they want to spend a lot of money on some kind of cosmetic,” said community activist Imani Henry. “But what we care about most is that they stop occupying our neighborhoods, stop murdering, harassing and killing black and brown people, stop police occupation in our neighborhood.”

But the plan raises a larger question: can a little more space, brighter walls and new furniture actually improve relations between civilians and police? Or is this a misguided attempt to fix a problem that’s far bigger than any renovation can solve?

Never in the NYPD’s history has the agency given its precinct lobbies a major renovation like this. Nor has it created a community meeting room inside a precinct, though it plans to do that for the first time with a new 40th precinct house under construction in the Bronx, said the building’s architecture firm, Bjarke Ingels Group.

In other cities, however, this idea is nothing new. Police departments have been designing stations with community in mind for decades, according to Ian Reeves, president of Architects Design Group, which specializes in public safety facilities and has offices in Orlando and Dallas. While police buildings historically emphasized security with less attention to aesthetics, that calculus has changed as officer-involved shootings have made community-police relations a national priority, Reeves said.

“Certainly, the fortress mentality is gone,” Reeves said. “I can’t remember a public safety facility that we would have worked on that didn’t have any community engagement space built into it in the last 20 years.”

The ripple effect of this architectural trend is visible in cities like Chicago, where the prototype for police stations has included community meeting rooms since the late 1990s, and Salt Lake City, where a new public safety headquarters boasts an open plaza and art displays, according to Jim McClaren, a senior principal on the project. Two years after Freddie Gray died in police custody in Baltimore, triggering riots against police, the city’s Western District police station got a community-oriented makeover. The new design, unveiled in 2017, has public restrooms, free Wi-Fi and a community garden, according to War Horse Cities, the project’s lead developer.

The hope is that friendlier-looking stations will help officers achieve the goals of community policing, according to Eric Piza, an associate professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. Many police departments are embracing community policing, which attempts to build trust by involving citizens in crime-fighting efforts, Piza said. “If the citizens have a terrible time every time they go to a precinct, and it’s not welcoming, and it’s the last place in the world they want to be, then that may be impeding on the policing mission.”

But if community policing is the greater aim, is spiffing up police stations the most meaningful investment? Instinctively, a nicer environment seems like it could ease tensions. There’s also broad evidence that changes in design can relax people and curb aggression. But many architects and police experts said they weren’t aware of any substantive research that showed how the design of a police station could benefit community-police relationships or trust at all.

Jim Bueermann, president of the National Police Foundation, says making an actual change in community-police interactions would likely require customer service training and new policies for officers staffing the space — more than just a physical redesign. Meanwhile, Art Lurigio, a criminologist at Loyola University Chicago who helped Chicago build its first community policing plan, thinks police departments ought to spend money on smaller, decentralized satellite precincts instead of existing stations. He thinks this would help spread police presence and familiarity to more high-crime areas. Research suggests substations like these can actually improve perceptions of police, while Lurigio says redesigning lobbies is a superficial fix.

“It’s an investment with a dubious payoff,” Lurigio said. “If the cage is gold, is it better to be in the cage?

NYPD Police Commissioner William Bratton introduced the idea of precinct redesigns to New York City in 2014. He felt strongly that, if done right, they could be essential tools to engage communities, according to Edna Wells Handy, who served as Bratton’s legal counsel during his tenure.

During his time leading the Los Angeles Police Department, Bratton had implemented ATMs and community rooms into police stations, aiming to transform them into safe, resource-rich hubs for citizens. It was part of his larger community policing program there, and he wanted to do the same thing when he returned to New York, where he had been commissioner in the 1990s. He asked Handy for help. So, she worked with Terri Matthews, director of the city’s Town+Gown program in the Department of Design and Construction. They enlisted local architecture and interior design students to create case studies of what a better precinct could look like. Because of its high crime rate, the 73rd precinct served as a model.

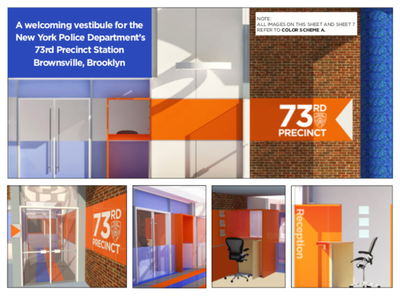

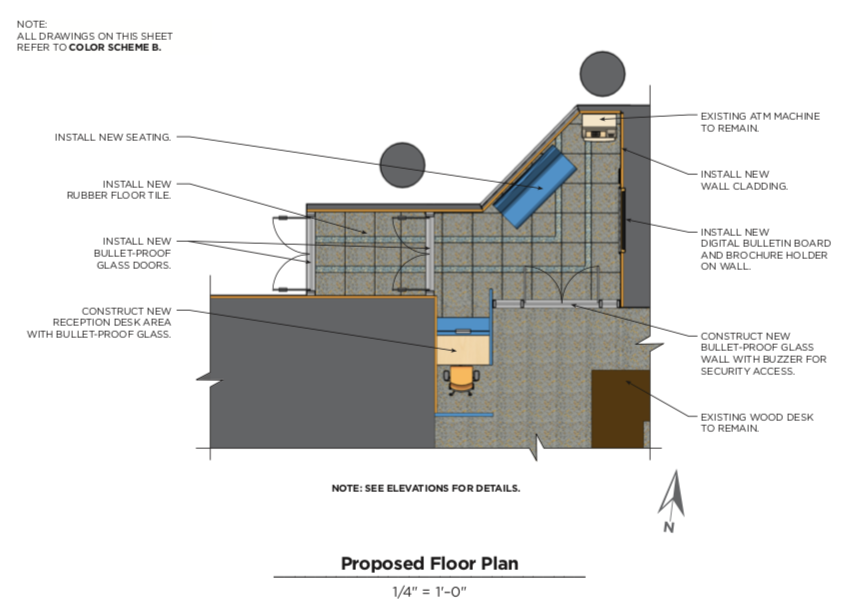

The results impressed the NYPD, the city and elected officials — “they were all gung-ho,” Handy said. New York School of Interior Design students had drawn up a lobby renovation that featured more color, light and signage with a comfortable couch and a barrier to make the reception area more private. Pratt Institute students had dreamt up a movable community connection pavilion that could sit in the 73rd precinct parking lot and serve as a flexible resource room for the public.

This floor plan, designed by students at New York School of Interior Design, is the initial inspiration for the lobby redesigns, which will start with the 73rd and 71st precincts, according to Edna Wells Handy (Photo courtesy of NYSID)

But even with initial support, the project lost steam when Bratton left the department in 2016. “We tried to restart it in a number of ways with the present commissioner, but that wasn’t his priority,” Handy said.

So, three years later, long after leaving the department herself, Handy was pleased to hear that elected officials were finally ready to invest in redesigning precinct houses. She scheduled a meeting with the Borough President’s office in early October, where she and others presented their work from three years prior as a starting point for the proposed renovations.

The city hasn’t decided how closely they will stick to the 73rd precinct case studies. It’s also still unclear whether they will implement community rooms either inside or outside the precincts. But as a starting point, the lobby areas of all four precincts are expected to be redesigned, Handy said. Soon, the group will meet with the NYPD to start planning.

Pratt Institute students designed the community connection pavilion as a resource room for the community at the 73rd precinct (Photo courtesy of Pratt Institute)

As the news of the project circulates through Central Brooklyn, reception is mixed. Graphic designer Tevin Frederick, who works in a printing shop across the street from the 73rd precinct, thinks a remodel of the lobby sounds promising. “If it will improve the relationship in the neighborhood with the police, if they will feel more comfortable to go in there and talk to them, then I say it’s worth it,” he said.

Lumumba Bandele, a spokesperson for Communities United for Police Reform, is more critical, especially following the NYPD’s announcement in August of a ban on videotaping inside public areas of precincts. “These renovations are an empty gesture, coming on the heels of NYPD unilaterally reducing transparency in these very sites,” Bandele said.

Despite criticisms, the precinct redesigns will soon be underway, with construction hopefully beginning in spring 2019, said Ampry-Samuel. She expects there will be opportunities for each precinct’s local stakeholders to determine their own needs. “The design itself comes out of the community conversation,” she said.

Meanwhile, the police department does not know whether a brighter, more pleasant lobby or a meeting room can improve relations between police and the communities where they work. Nor, for that matter, does Ampry-Samuel, Adams, Handy or Mascol.

But New York City, like many other cities have done before, is trying it out anyway. If something good can come of it, they say, it’s worth it.

“It’s such an important idea,” Handy said. “We just can’t let it die.”

Follow Ali Swenson on Twitter @aliswenson.