The New York City Council passed a pair of landmark police-reform bills Tuesday — one by a wide margin and one more narrowly — that aim to impose strict rules on how NYPD cops search and question New Yorkers.

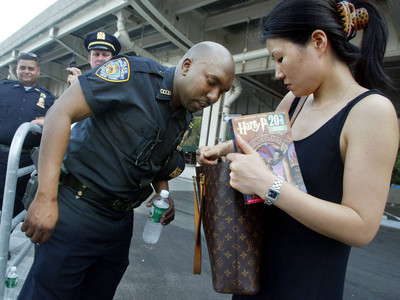

Introduction 541-C, which would require the NYPD to instruct officers on how to get consent from people they search without a warrant, passed 37 votes to 13 at the Council's last meeting of the year. The bill would also require the Police Department to develop policies for recording such searches and explicitly telling civilians that they can refuse to be searched.

Introduction 182-D passed by a much smaller margin of 27-20, with three members abstaining. It would require officers to show business cards to anyone they search or question and explain the reason for the search or questioning, except during traffic stops and other certain circumstances.

The pair of bills, known as the Right to Know Act, survived a full Council vote even after a compromise on Introduction 182-D led several progressive lawmakers to pull their support. They argued the bill carved out too many exceptions, leaving New Yorkers vulnerable to illegal searches in the most common encounters with police.

"I am convinced from three years of negotiations and from my own lived experience that this bill will have a real impact in improving the day-to-day interactions between police and civilians," Councilman Ritchie Torres (D-Bronx), the lead sponsor of Introduction 182-D, said at a news conference before Tuesday's vote.

The bills now go to Mayor Bill de Blasio's desk. The mayor spoke supportively of them last week after a long period of skepticism.

Torres brokered the final version last week with de Blasio and the NYPD. Rejecting criticisms that he submitted to the NYPD's desires, Torres called the bill a "hard-fought compromise" that the Police Department has only "begrudgingly" accepted.

Torres suggested passing the original identification bill could have led to a work stoppage or lawsuit from the NYPD, which would stop it from doing any good. Implementing the law with buy-in from police will make it more effective, he said.

"If we can pursue a path to police reform without provoking an upheaval in the NYPD, then why not do so?" Torres said.

The Right to Know Act bills were first proposed in 2013 as part of a broader legislative effort to reform the NYPD after its stop-and-frisk program was found to be discriminatory. The random searches aimed at snuffing out low-level crime disproportionately targeted people of color.

Their approval represents a partial victory for police-reform and social-justice activists, who wanted Torres' identification bill to go further.

Dozens of advocacy groups, including the influential Communities United for Police Reform, opposed Torres' compromise. Several progressive Council members followed and split their votes, supporting the consent-to-search bill but rejecting Torres'.

Those lawmakers argued the compromise not require cops to identify themselves in the majority of their interactions with civilians, such as when they routinely ask someone for identification. It's crucial to have a mechanism for accountability in situations like those that have historically been abused, they argued.

"This is not about compromise. This is about compromise that is worth it," Councilman Jumaane Williams (D-Brooklyn) said.

Lawmakers cited their own encounters with police and the high-profile deaths of Eric Garner and Sean Bell at the hands of cops as evidence of how badly the protections are needed.

Both bills also faced opposition from the right, with Republicans and moderate Democrats worrying it would endanger public safety by constricting cops too much. The NYPD Patrolmen's Benevolent Association, the city's largest police union, suggested they would make it harder for officers to stop terrorist attacks.

The bills come with a cost. The NYPD expects to spend $5.9 million next year on the business cards that cops will have to carry under Introduction 182-D. It will cost the Police Department another $650,000 in 2019 to create a database required by Introduction 541-C.

The approvals marked a win for Torres and Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, who presided over her last Council meeting on Tuesday. She supported Torres' bill and praised his work toward a compromise.

The debate over Introduction 182-D created a rift between Torres and some of the other seven candidates for Mark-Viverito's speaker post. Williams, along with Brooklyn Councilmen Donovan Richards and Robert Cornegy, voted against the compromise.